Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman were jointly awarded the 2015 ACM A.M. Turing Award today. Their 1976 paper, New Directions in Cryptography, essentially created asymmetric cryptography. Today, asymmetric cryptography secures our online communications—from PGP-secured texts, emails, and files, to TLS and SSL-secured websites (including this one). So how does asymmetric cryptography work, and how is the Diffie-Hellman key exchange more secure than older methods of encryption?

Symmetric encryption

Symmetric encryption relies on a key shared between two or more people. A message is encrypted using this key, and can then be decrypted by the same key held by somebody else. Think of it like the front door of a house. Alice has a key to the door, so she can lock and unlock the door. Bob also has a key, so he can also lock and unlock the door. In fact, anyone with a copy of that key can both lock and unlock the door whenever they want. In the case of a message, this means that anyone with the right key can encrypt (lock) the message, or decrypt (unlock) the message.

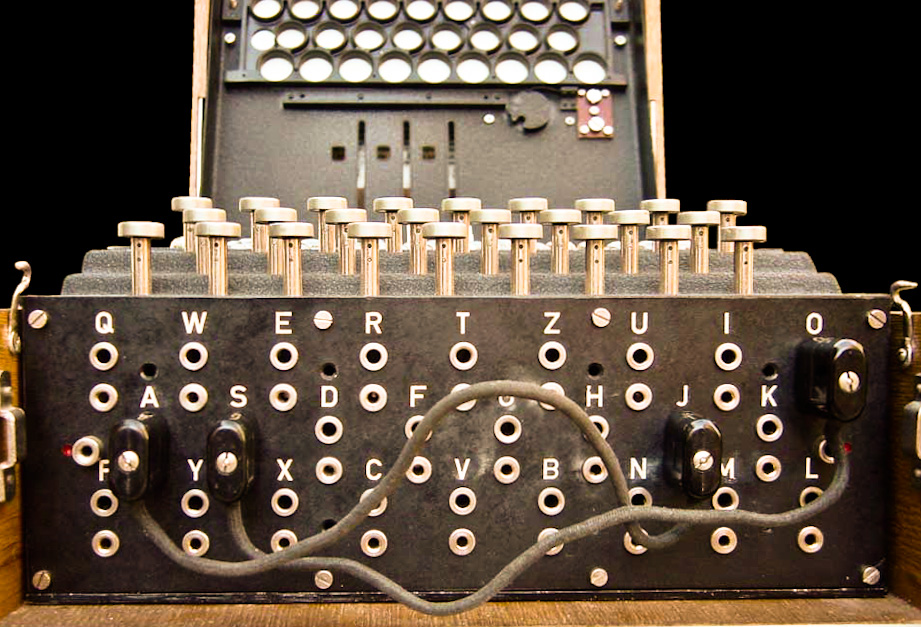

It’s possible to break symmetric encryption , though it takes time. Perhaps one of the most famous examples is from World War II, when the Allies were struggling to crack encrypted Nazi communications. The encryption was created with a key that changed daily, and through the use of the Enigma machines. The cryptography was eventually broken, but largely through the skill of the codebreakers, poor operating practice from some of the German operators, and the capture of key tables and hardware by the Allies.

Asymmetric encryption

Asymmetric encryption, in contrast to symmetric encryption, uses a pair of keys to encrypt messages. One of the two keys is made public to everyone, and one is kept private (the two types of keys were called, cleverly enough, the public key and the private key, respectively). Messages encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted using the private key , which ensures that the contents of the message can’t be read by anyone except the holder of the (hopefully secure) private key. So if Alice wants to send an encrypted message to Bob, she starts by finding his public key. She then encrypts her message using that, and sends it to Bob. When Bob receives it, he uses his private key to decrypt the message. If he wants to respond, he can encrypt his reply using Alice’s public key, and the cycle continues. Since the public keys are usually published or exchanged in a way that lets each party be confident that it belongs to whomever they are sending it to, this ensures that the identity of the recipient can be verified. Alice knows that only Bob can unlock her message, and Bob knows that only Alice can unlock his.

This is commonly used on websites that are secured by SSL/TLS (including this one). Pretty much every major website is secured via SSL, and browsers will display a green padlock in the address bar of secured sites. This serves two purposes; it will prove that the website belongs to whomever it purports to belong to, and it encrypts traffic between your computer and the website so that it can’t be read by attackers, your ISP, or others who may have a vested interest in what you do.

This works in exactly the same way that the messages between Alice and Bob did. When you visit a website secured with SSL, your browser and the server exchange public keys. The server encrypts traffic to you using your public key, which your browser decrypts. And your browser encrypts traffic to the server using the server’s public key, which the server decrypts. Anyone trying to listen in on the conversation your browser and the server are having will hear nothing but random gibberish. There’s one additional thing that your browser does to ensure that it’s not talking to a fake server that’s pretending to be the real website: it takes the public key presented by the server, and it compares it to a repository of public keys. If it matches, it’s the real server. If it doesn’t, it could be an imposter– and somebody could be listening in.

So the next time you’re wandering around the web, take a minute to appreciate that little green padlock in the corner of your screen, and think about the incredibly complicated math that underpins security on the internet. It works invisibly to keep your communications safe, secure, and most importantly—private.

I’m not a cryptographer or a security specialist, just somebody who enjoys reading and learning about security. If you think I left out something important, please send me an email so I can fix it.